Piecing Together the Ultimate Waterfowl Gun

Aldo shakes off after retrieving this Canada goose.

The average number of days spent waterfowl hunting, per season, for over 50% of duck hunters is less than ten days (National Flyway Council study in 2018). For most, having a well-functioning and reliable shotgun will be more than enough for the handful of duck hunts that occur each year. But, for me, and likely a few of the ~ 40% of hunters that spend more than ten days a season in the marsh, a shotgun that’s been purpose built, and/or modified, for waterfowl hunting is something of sincere interest. I do want to point out that for those that are new to hunting and shooting, or just new to waterfowl hunting, the recommendations below should not serve as prerequisites to having an exceptional waterfowl hunt, nor can these recommendations replace the knowledge and personal preference one attains through personal experience and time spent afield. Rather, these recommendations provide an insight to my own preferences, hunting experiences, and practices - they should not be treated as anything more substantial than that. There simply is no “one size fits all,” especially when spanning multiple disciplines, or multiple species of pursuit; but for those, such as myself, that have a curiosity for efficiencies and nuances, and that value the journey leading into the pursuit just as much as the pursuit itself, there is much that can be discussed when seeking a purpose-built shotgun tailored to waterfowl hunting.

This article is broken into two sections. The first focuses on the core functional aspects of a shotgun, out of the box, that create the foundation for a great waterfowl gun. The second hones in on after-market modifications and DIY gun-smithing to further maximize a shotgun’s efficiencies regarding waterfowl hunting. Click here to skip ahead to the second section.

My journey to find, or piece together, the ideal waterfowl gun, and for this gun to earn the namesake Marilyn the Mallard Mauler, started with an after market choke tube. After that? Well… have you ever read the story, If You Give a Mouse a Cookie? (In Laura Numeroff’s classic children’s book, a mouse approaches a cookie-gripping adolescent boy and pleads the case for the boy to share the cookie. The boy concedes and not long after, that mouse is back and asking for more. This time he’s asking for milk. It’s a great way to introduce the concept of a slippery slope to a young reader. Or, any reader, for that matter.) The point is - I made one minor modification to my gun, just like how the boy gave the mouse a cookie, and before I knew it, I was on the hunt to identify how else I could maximize efficiency and improve my shotgun’s capabilities (but all within my own skillset and means and with turning a blind eye to Benelli’s custom shop).

I’ll start with the foundation of what makes the perfect waterfowl gun - the action of the gun itself. There are bolt action shotguns, break action shotguns (such as side-by-side, or SxS, over-and-under, or O/U, as well as single barrels), pump action, and semi-automatic shotguns. Bolt actions are often only observed in gun collections or vintage gun dealer racks thus I immediately omit them from consideration for a waterfowl gun. Single barrel, break actions are similarly vintage or, in some cases, modern but clearly intended for youth shooters, thus I will omit these from consideration as well. Pump action shotguns can be extremely durable, reliable, and affordable but the manual intervention required (the pumping) can adversely impact a hunter’s point of aim and overall “swing through” on the bird. It's simple engineering and durable reputation stand to make a pump gun an excellent “backup gun,” as well as a new hunter’s first gun where curiosity and experience outweighs budget, but the interference that the pumping action innately introduces into the mechanics of shooting is why I’m omitting the pump-action shotgun from the running.

That leaves break action double barrels and semi autos in consideration. I am a huge fan of the side by side shotgun (a 28ga CZ Sharptail SxS is my go-to upland bird gun) but when it comes to pursuing waterfowl, the unique flexibility that the two barrels of a SxS can add to a hunt (via the possibility of two different chokes and two different loads, all in one gun at the same time) do not, in my opinion, carry-over into the marsh to justify the glaring trade-off between a double barrel and an autoloader: the ability to squeeze off two shots v. three, respectively, before reloading. I do want to clarify, though, that this preference of being able to take three shots over two is not to be attributed to a blind “more is better” attitude. Having the capacity and option to take one more shot, regardless of need, is always going to be appreciated. However, in this case, this third shot is not defining because of its quantity, it is defining because of the way waterfowl hunting is typically conducted.

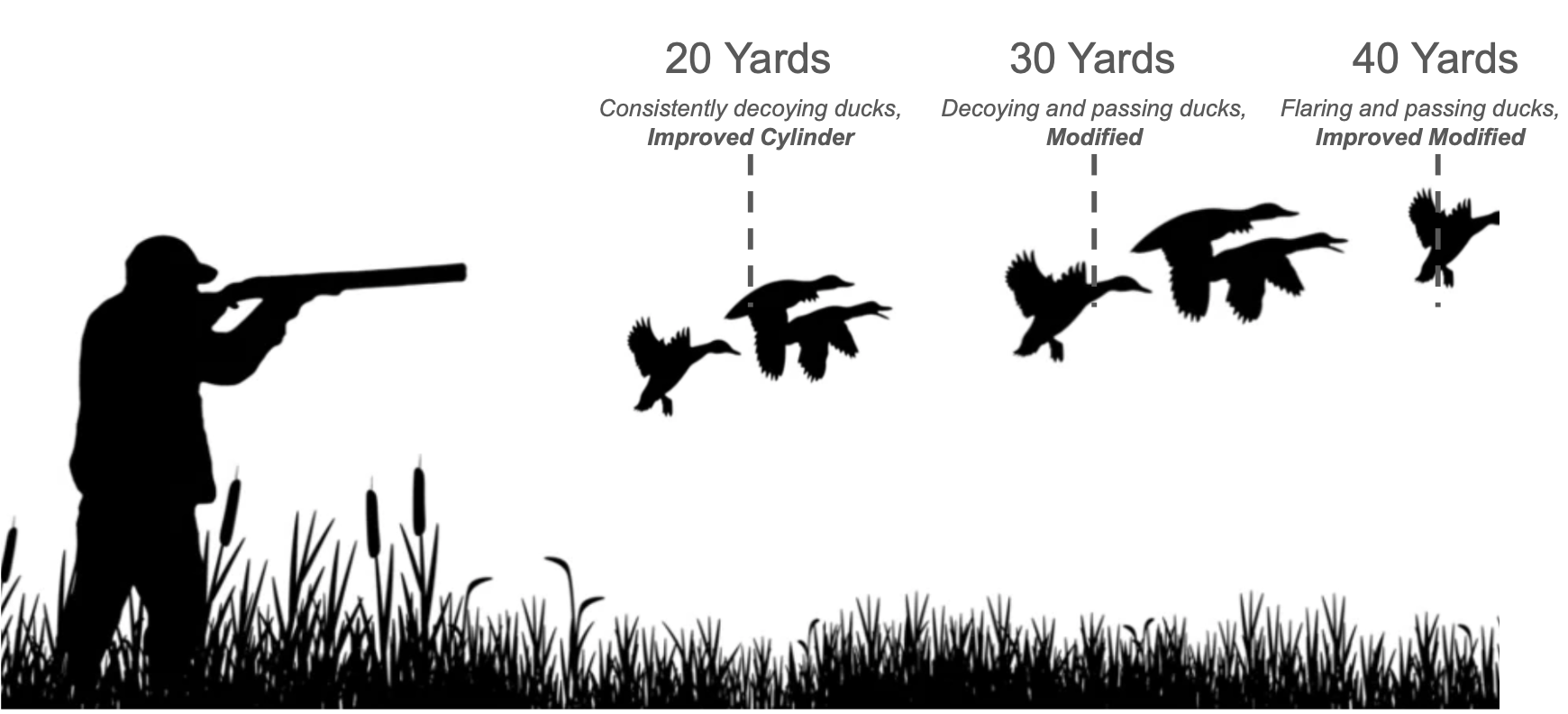

Most waterfowl hunts present a scenario in which the hunter is relatively static for the duration of the hunt. This is unlike an upland bird hunt where the hunter and his dog traverse great stretches of terrain to seek out their quarry. Conversely, on most waterfowl hunts, the hunter will set out decoys, tuck away in a hiding spot (sometimes referred to as a “blind” or a “hide”), and then, in an effort to attrack their quarry, the hunter will begin weaving a chorus of notes with an artificial duck call with the intent to mirror the cadence, conversation, and instincts of wild ducks. (Note this key difference in pursuit - seek vs. attract and remember this as we review the spatial procolivity for these two distinct forms of hunting, upland and waterfowl.) As the ducks begin to fly into the sound of the calls, and to the sight of the decoys, a window of shot opportunity begins for the hunter as soon as the ducks fly within range. This can last for as long as the ducks continue to “work” the decoys - flying down, and towards, the hunter or passing left and right of the hunter. Often times waterfowl will circle and return to shooting range multiple times before succumbing to their mistake or realizing that it’s time to get out of Dodge.

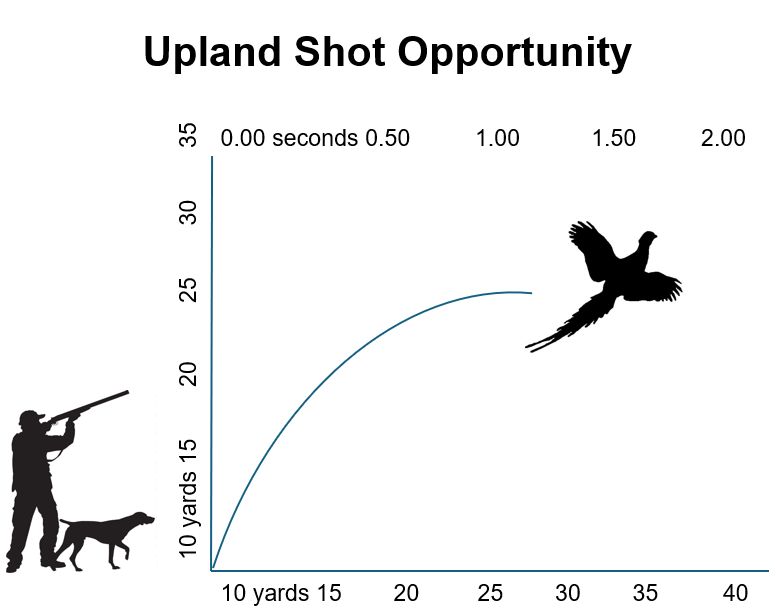

That was a bit of a mouthful, so I’ll try and articulate that with visual aides now. Reference the first pictogram, “Waterfowl Shot Opportunity.” The bottom X-Axis denotes the distance of the duck from the hunter while the top X-Axis portrays an arbitrary time value. As the shot clock increases, the ducks are depicted as closing the distance out from 40 yards closer to 10. The u-shape curve demonstrates a flight pattern: ducks are flying towards the hunter, the shot clock is running and the opportunity to take a shot continues as the ducks fly closer. At some point the ducks may flare, whether out of wariness or from the start of the shooting, and they will begin climbing higher and back out of range (here’s where the Y-Axis comes into play, showing the altitude of the ducks). The key takeaway here is that in many waterfowl situations the distance at which a hunter will be from his quarry can be predictable and it can also remain, within an expected deviation, constant throughout the hunt. This is predictable in the sense that hunters often see ducks on the horizon, or in the sky, and can anticipate the duck’s arrival and, thus, the hunter can often choose when to take a well-placed shot, often just over the decoys (which are often set at a known-distance, well within shotgun range, from the hunter’s blind).

Typically the ducks are flying towards the hunter or passing by and, in either circumstance, this creates something of a window of opportunity for multiple shots.

Now let’s look at the upland hunter that is not static and is actively searching for their quarry. When the grouse or quail of rooster in question is found, by wild flush or steady dog, an upland bird is frequently flying up and away from the hunter. (Quick, recall the duck hunter and his situation. He is often observing the ducks at a distance, growing closer, from either straight on approach or from a lateral approach.) The upland bird hunter has a finite amount of time to mount the gun, point, and begin shooting while the bird is getting further away and, eventually, out of effective range. I have attempted to highlight this contrast of bird flying away, compared to flying parallel or approaching, with the second pictogram, “Upland Shot Opportunity.” Here, the bottom X-Axis denotes the distance of the pheasant from the hunter and the top X-Axis portrays an arbitrary time value. This is the inverse of the “Waterfowl Shot Opportunity.” The shot clock starts as the bird flushes and that clock quickly dwindles as the bird flies up (Y-Axis) and away from the hunter.

When found, by wild flush or steady dog, the upland bird is frequently flying up and away, immediately starting the very finite “clock” of a shot opportunity.

So here’s where the double barrel shines, and the auto loader takes a back seat. Having two barrels means two chokes and, I’m getting a bit ahead of myself now as you’ll read more later on choke selection, but the gist of it it is that, in many upland scenarios, having the organic ability to take two shots, each choked differently for different ranges, can be extremely advantageous. This, of course, is not available to the autoloader shooter with his one barrel and single choke, but it is not nearly as applicable in the waterfowl scenario anyway. Thus, the two barrels, with two constrictions and the advantage that brings to the upland hunter, at the cost of a third shot, does not warrant the trade off in the marsh, where distances are known and shots predictable. This is why the third shot of an autoloader tips the hand in favor of choosing an autoloader as the action of choice for the ideal waterfowling piece today.

As an aside, many autoloaders today incorporate ergonomic enhancements that alleviate recoil that are often unavailable in doubles. Waterfowl loads are frequently heavy and hard-hitting so stocks like Benelli’s Comfort Tech 3 or Beretta’s Kick Off are quickly appreciated after discharging a few 3” or 3 1/2” magnum loads at 1400+ FPS.

There is, of course, a litany of variables to take into account with these two over-simplified depictions. Payload, velocity, species of bird and its rate of travel, wind conditions (pushing against the bird to slow it or pushing up and behind the bird which helps increase the bird’s flight speed), age and health of the bird, among many others will influence the “shot opportunity;” we’re omitting all of those for the sake of a simple comparison and explanation of how a double barrel gun is likely better suited for the uplands while an auto-loading gun can be a great fit for the marsh.

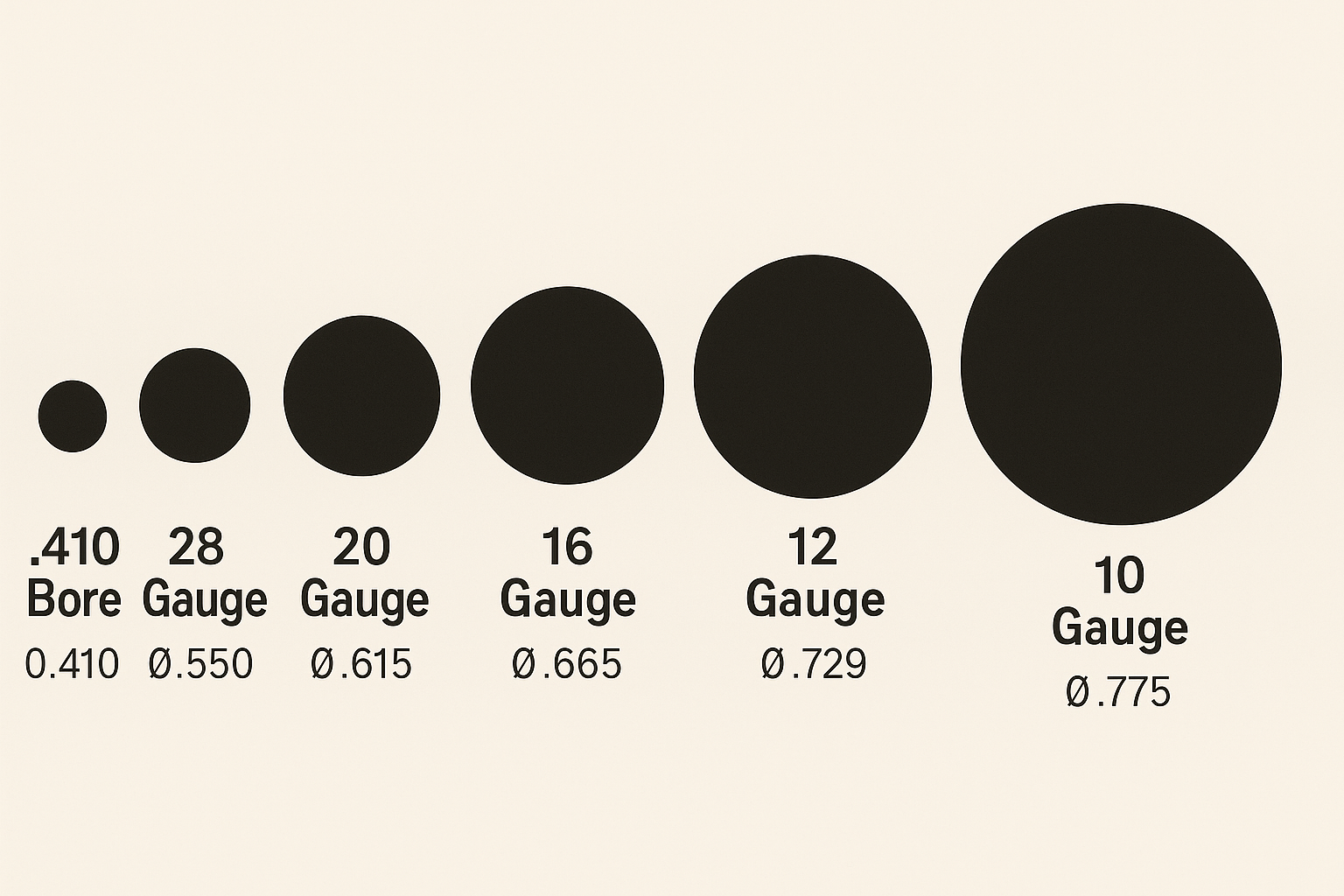

With the action of the shotgun now discussed, I’ll turn to gauge (or bore). Today’s shotgun manufacturers tend to produce .410, 28, 20, 16, 12, and 10 gauge shotguns with the marketshare tipping largely in favor of the 12 gauge. Selecting a gauge is as critical, or irrelevant, as the shooter makes it out to be. For the simplest, and most economical, route, the 12 gauge is easily the answer. But for those seeking a bit more contemplation, I’ll step through each of these.

The most common shotgun gauges relative to one another. The numbering, such as “0.729,” represents the diameter, in inches, of the bore. Bore diameters have been relatively standardized in the modern era but there can still be a deviation from manufacturer to manufacture, time period to time period. The number of the gauge, such as “12,” hails from mid-17th century England where it would take twelve lead balls, of this diameter, to equal one pound of lead.

.410 - The smallest of today’s manufactured bore sizes, the .410 is often associated with youth and new shooters due to the overall smaller frame, or size, of the firearm as well as the extremely moderate recoil that results from such a small payload. Even in the best of conditions, this bore is likely not suitable for any waterfowl hunting and it is notorious for poor patterns but it can still serve as a great teaching tool for a young hunter or as a backyard snake killer.

28 - Lightweight but surprisingly capable, the 28 can be considered to be an excellent upland gun where the payload is large enough to accomplish the task at hand, but small enough to ensure there’s still something left to eat after the hunt. Recent advances in shot shell ammunition have aided in improving the 28’s range and versatility. Benelli started manufacturing a waterfowl-specific Super Black Eagle 3 in 28 gauge in 2022 but shooter be warned, while this is still capable gauge, this is only a realistic option in the marsh in the hands of an experienced shooter and with close decoying ducks.

20 - I’ve watched this versatile bore adapt, largely in part, like the 28, due to advances in shot shell ammunition, from being the preferred choice for youth and women to being a serious contender for all body types and experience levels. If I was to only hunt with one shotgun all year, I would seriously consider the 20 as it splits the difference from the 12 gauge staple (with it’s heavy weight and hard-kicking recoil) and the niche 28 (with it’s light weight, low recoil, but limited range).

16 - Sometimes referred to as the “Sweet Sixteen,” those who have had the opportunity to shoot one tend to champion it. But given how difficult it can be to find ammunition for this gauge, and with only a small handful of modern shotguns being manufactured in this gauge, this is something of a non-starter given its logistical and economical challenges.

12 - As Olympic shooters began gravitating to 12 gauge in the 1950’s and 1960’s, consumers (and hunters) quickly followed suit. Since then, the 12 gauge has become the most common bore manufactured for both competitive shooting as well as hunting. With economies of scale at play, it is now the most affordable, both in terms of the firearms themselves, as well as the ammunition, to shoot. It also boasts the widest range, again both in terms of firearm itself as well as ammunition, of options from a wide array of manufacturers. Note that the recoil in a waterfowl hunting round can be significant, especially when compared to any of the “sub gauges” (i.e, any shotgun smaller than a 12 gauge) and some shooters may report discomfort from lengthy shooting sessions.

10 - This dinosaur blaster can trace its roots to market hunting days where a bigger bore potentially meant a bigger bag (and, therefore, a bigger paycheck). The 10 gauge has seen something of a resurgence in recent years, particularly marketed towards dedicated goose hunters. Modern firearm options are limited as is 10 gauge ammunition and the recoil is quite substantial. I would not recommend this to anyone other than a zealous goose hunter.

When I purchased the shotgun that eventually turned into Marilyn, I didn’t do very much upland hunting, but I did quite a bit of waterfowl hunting in a flyway where both ducks and geese are prevalent. That, paired with the economics of buying 12 gauge ammunition, is why I ultimately ended up going down the 12 gauge path. And, if not for the occasional goose hunting I do each year, I would seriously contemplate a 20 gauge for my dedicated duck gun today, especially given the ammunition improvements in the last few years.

A two-man limit of geese is not the norm for my waterfowl hunting, but the opportunity to take a shot at a goose occurs enough that I feel more prepared heading afield with a 12 gauge than something smaller, such as a 20 gauge. If big Canadas like these weren’t in our flyway, I would seriously consider using a 20 gauge as my dedicated waterfowl gun. (If you look close enough, you can spy the bands on the two geese my brother-in-law and I are holding up.)

We’ve stepped through action and bore, two of the largest differentiators among shotguns, but there’s a few more things to consider such as operating system. Generally speaking, in terms of auto-loading shotguns, there are two camps: inertia and gas operation. Each has its merits, just as each has its drawbacks, too.

A gas-operated shotgun is going to funnel the gases expelled from the combustion of the ammunition back through the gun to force select mechanical components to move. Gas guns inherently require more maintenance as they are funneling the off put of the ammunition’s combustion through gas valves and tubes, which will result in carbon build up over time that can then clog and cause the gun to not cycle. However, as long as the shooter is diligent about maintaining their shotgun, this is typically not a real issue and, because gas valve can be “tuned” or adjusted, the shooter can find the sweet spot of letting just enough gas through the tubes to cycle the next shell, while expelling all remaining gas which, in turn, reduces recoil (less gas pushing back into the gun itself and instead exiting outward through venting).

Gas: relies on gasses being funneled out of the barrel and back into the action to cycle the gun.

CON: Requires diligent maintenance to prevent carbon build up blocking the gun from cycling; this can be particularly important in extreme wet and cold conditions where particles can “gum up” and prevent the gun from cycling

CON: Requires some “tinkering” to find, based off what ammunition is being used, the ideal amount of gas to funnel back into the action and amount to expel from the firearm

PRO: Because how much gas is utilized v. expelled can be finely tuned by the shooter, gas guns can typically cycle just about any kind of ammunition just as long as the gas is tuned accordingly

PRO: The lowest felt recoil can be achieved respective of a particular shotshell load with dedicated gas tuning

An inertia-operated shotgun is going to use the inertia from the ammunition’s combustion to force select mechanical components to move. These require no adjustments in any manner similar to that of adjusting a gas gun’s gas rings and valves, or additional cleaning like a gas gun, but some inertia guns struggle to cycle low-energy loads. Game loads are traditionally heavier - more powder, more payload - than target loads for games like trap and skeet, and these game loads typically create enough inertia for these modern guns to cycle without issue. However, some inertia guns will struggle to cycle lighter loads which is why inertia guns are uncommon in competitive shotgun shooting.

Inertia: relies on the inertia generated by the ammunition’s combustion to cycle the gun.

PRO: No tinkering required

PRO: Thrive in austere and wet conditions

CON: Sometimes struggle to cycle “light” shot shell loads like those used in target sports such as skeet and trap

CON: More felt recoil, especially with game loads, than compared to tuned gas guns

In the context of a dedicated waterfowl gun, I recommend an inertia-operated shotgun for its reliability in extreme weather as waterfowl hunting often occurs in cold and wet climates where these conditions can set the stage for carbon, oil, and other matter to congeal which, in turn, can adversely impact a gun’s cycling. I also don’t participate in any formal shooting sports, such as trap or skeet, so whether or not the gun can consistently cycle light target loads is irrelevant. But for those that are looking for even more information on these two camps, here’s a great article that goes into a bit more detail on the differences of the two.

I once borrowed a gas-operated Beretta to jump a cattle pond full of ducks. The first shot notified the ducks of my presence, but the other two shots didn’t come to fruition as the gun had gummed up. The gun had sat out in the truck overnight in extreme low temperatures. That, paired with the gun not being cleaned recently, resulted in the action getting “gummed up.” By the time I realized what happened, cleared the chamber, and re-loaded, the ducks were well out of range.

Lastly, before we discuss after market or custom shop modifications, we should briefly touch on barrel and finish. Finish should not be a serious consideration, especially to the backdrop of all of the other criteria discussed thus far, as it is relatively easy to change with a great deal of both DIY and professional services available. I personally prefer flat black for its inconspicuous nature, and the fact that it will blend with just about anything, but depending on the year, make, and model, various finishes are available across various patterns and camouflage brands. The barrel length, on the other hand, may seem like an afterthought for many but certainly merits consideration. And I say that as someone who has bought several shotguns before learning that various barrel lengths even existed, let alone the benefit to one length over the other.

Modern hunting shotgun barrel lengths span from 24 to 32 inches with 28” being the most common. Competitive shooters will lean towards the longer barrels, 30 and 32 inches, as these lend themselves to be a bit more heavy which aides in building momentum for smoother swing of the gun. In static environments, such as a shooting competition, or sitting in a duck blind, the extra weight from a long barrel, and any other spatial concerns of, for example, swinging and whacking the barrel into a tree, are largely irrelevant. On the other hand, the upland bird hunter that may be carrying their shotgun for eight hours at a time and need a quick, snappy swing, the lighter weight of a shorter barrel, paired with it’s smaller spatial footprint, is something to seriously consider. But, for waterfowl hunting, 28 or 30” barrels are going to be just fine. 28” is slightly more versatile but, of all the things discussed here today, differentiating between two inches of a barrel need not be the focus or a deal breaker at the gun counter.

Let’s take a moment to recap where our ideal waterfowl gun criteria now stands:

Semi-automatic

12 gauge (unless geese are off the menu, in which case, 20 gauge)

Inertia-operated

28” or 30” barrel length

Durable finish

Believe it or not, even with these criteria determined, the list of options is still fairly extensive. Something akin to narrowing down your car shopping from “all motor vehicles” to “all SUV’s, crossovers, and pickup trucks.” Did you narrow down this list? You sure did. Is it still really long? It sure is. Next step? Test drive. Except, with firearms, there really aren’t a lot of great “test drive” options due to laws surrounding firearm ownership and purchasing. If and when possible, though, look for opportunities to handle and shoot as many shotguns that you can get your hands on because you will eventually find that you do, in fact, have preferences which can influence your purchase (or gunsmithing / modification plans). Whether that’s the location of the safety (say, to the front of the trigger well on a Beretta but at the rear of the trigger well on a Benelli) or the weight and swing of a 30” barrel instead of a 28” barrel, every shooter will develop their own preferences in both a firearm’s form as well as its function.

You will also discover, in those instances that you get to actually test drive (shoot) a gun, that you inherently, for whatever reason, seem to shoot one gun better than another when swinging on targets, be that clay or bird (another reason why handling and shooting as many guns as possible is beneficial is being able to learn that more clays turn to powder with Shotgun A than with Shotgun B). This differentiation can be a combination of factors but the most influential of these will be how the shotgun “fits” its shooter. Things like length of pull (LOP) and comb height are two examples of these fitting considerations. Many shotguns today, out of the box, will include components, like shims and drop plates, to make minor stock adjustments to accommodate a wider spectrum of shooters. Allowing customers to make minor adjustments, with included parts, helps cut down on the volume of models or variations that shotgun manufacturers produce. The trick, of course, is understanding what adjustments to make which is where shotgun fitting comes into play.

Finding a shotgun’s fit isn’t as easy as finding a shoe size but there are resources online to help (here’s a great article that goes more in-depth on shotgun fitting) and chances are, your local gun shop or trap range will have someone floating about that can point you in the right direction. This is something that is often overlooked, or perhaps even unknown, to many hunters today, but understanding how certain dimensions on a shotgun can align with your body is one more step forward in buying a shotgun that you will shoot well, or, at least, helping you understand what modifications to make to a shotgun to maximize its performance for you.

We’ve now covered the basic functional components that are preferred in a dedicated waterfowl shotgun out of the box. Now it’s time to talk recommended after-market modifications.

From muzzle to stock, we’ll now review:

Choke

Bead

Forcing Cone

Charging Handle

Bolt Release

Safety

Trigger

Recoil Spring

Recoil Pad

Sling

Choke

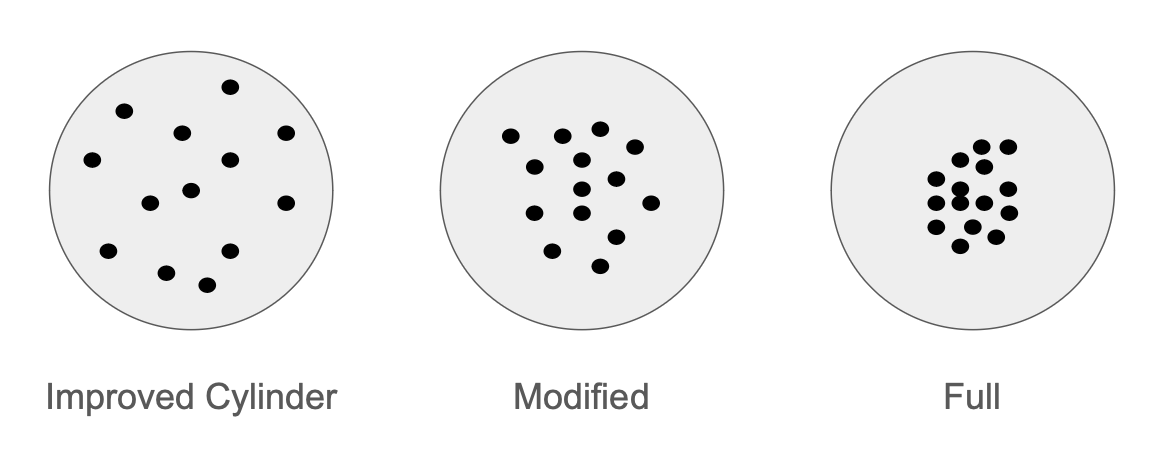

A choke tube is a small, interchangeable insert that screws into the muzzle end of a shotgun barrel. Its purpose is to control the spread of the shot pattern as it exits the barrel. A tighter diameter, or choke, such as Modified, will constrict shotgun pellets so that the pattern of these pellets remains more dense over a further distance. A wider choke, such as Improved Cylinder, facilitates a wider pattern where shotgun pellets begin to disperse at a quicker rate, and result in a wider pattern. Running from widest to tightest, common choke tube sizes are: Skeet I, Skeet II, Improved Cylinder, Light Modified, Modified, Improved Modified, Light Full, Full, Extra Full.

Examples of how different choke constrictions deliver different pattern densities when all things are equal (same gun, same ammunition, same distance to target).

Interchangeable choke tubes, which can be changed by the shooter by simply unscrewing one tube and replacing it with a different one, are commonplace now but that was not always the case. Pre 1960’s, shotgun barrels were manufactured at a certain diameter, or choke. Customers would need to decide, at time of order or purchase, not just the gauge and finish of a particular make and model of a shotgun, but also the choke of the barrel. Some shotguns came with multiple barrels so that a shooter could swap out a barrel to achieve the desired pattern density from one hunt to the next and, in that same vein, barrels of varying chokes were sold separately as well. It was not uncommon for double barrel shotguns to have two distinctly choked barrels where one barrel, for example, could be Improved Cylinder for close, pointed birds while the second barrel, for example, could be Light Modified, for when the first shot was a whiff and the bird is now in flight and further away from the hunter. Choke-specific barrels began to fade into history when Winchester introduced the “Winchoke System” to the American market 1969, the first mass-produced interchangeable choke tube system, and by the 1980’s, other manufacturers followed suit.

Choke tube manufacturing has since grown beyond the purview of the firearm manufacturing floor and there are now several well-established firms, names like Carleson’s and Briley, that specialize in choke tube development and production. Part of what keeps those businesses thriving is the frequency at which manufacturers produce new models of shotguns as well as the continued development and improvement of shot shell ammunition. In fact, what’s particularly tricky about selecting a choke tube is how closely woven its performance is tied to the ammunition it’s being fed. A glaring example of this would be Carlson’s line of chokes designed specifically for Federal Premium’s Black Cloud waterfowl ammunition. When Black Cloud first came to market, a number of hunters noticed parts of the shot shell’s plastic wad getting caught up on the ported edges of their choke tubes. This would impede the “flow” of shot through the choke, and out of the gun, resulting in poor patterns and poor terminal performance. Carlson’s was one of the first choke tube manufacturers to develop a choke tube designed specifically to maximize the performance of Black Cloud.

Continuing with the Black Cloud anecdote, a “chicken or the egg” type scenario begins to manifest. Is the ammunition driving the choke selection? Or, is the choke selection driving the ammunition choice? Choke A may pattern Ammunition A well, but when paired with Ammunition B, the pattern leaves something to be desired so the search for the symbiotic trifecta of shotgun, choke tube, and shot shell can quickly turn into a lengthy journey. That being said, it’s a journey that can pay the dividends of fewer crippled birds, fewer missed shots, and more birds in the bag so it’s highly recommended to put some time and effort into at least finding a functional trifecta. This can quickly turn into an exhaustive science project, testing this choke with that load, at this distance and then with that gun, and so forth but, I think it’s fair to say, most don’t have the time or the willingness to spend the money it would take to test every single permutation so let’s look at a few ways to narrow down the options.

We can start by looking at the shotgun make, model, species of pursuit and style or practice of hunting. In the case of a waterfowl gun, options can be further filtered just by understanding that all migratory bird hunting across the United States mandates that hunters can only utilize non-toxic shot. We can remove several choke options off the table by only looking at those that are compatible with, or maximized for, non-toxic shot. From there, and after filtering options out by firearm make and model, let’s look at common practice to date. Do you tend to shoot whatever ammunition is on the shelf at Wally World on your way to the marsh? Do you have a Smörgåsbord of ammunition that you inherited? Perhaps you can’t help your curiosity and you find yourself buying the latest innovated shot shell ammunition every season? If you have flats of shells already on hand, of the same type, then you’re likely best-suited to look for a choke that pairs well with that particular ammunition. If you prefer hunting with bismuth over steel, then you can look for choke tubes that are tailored to bismuth. There’s no right or wrong answer, but they are questions worth asking for the sake of your own time and money so that you make the most of a patterning exercise.

Patterning is absolutely critical to maximizing your gun’s capabilities. In fact, I would place this as only second, in terms of significance of things a hunter can do to maximize their efficiency and lethality afield, to getting fitted and understanding what shotgun dimensions are ideal for your particular anatomy. There’s a few schools of thought on how to pattern a shotgun (such as Steve Rinella’s MeatEater article or this article from Hunter Ed) but, in short, what we’re looking to understand is how a particular shot shell ammunition and choke tube combination perform together at a set distance.

Choke tubes start to pile up, literally and figuratively, over the years as varying shotguns come and go from the gun rack.

The first time I patterned Marilyn and tested a couple of different chokes I set a budget for myself based off my own historical use. I knew that I was only willing to spend $X - $Y per box of ammunition at any given time so I purchased a handful of boxes of different ammunition that fell within that price point. While I couldn’t eliminate every single variable from box to box, I did my best to select as similar of a payload as possible (1 1/4 oz, #4 shot, steel), and set out to put a few of each through each choke tube. The results were eye-opening and helped guide my ammunition purchasing moving forward once I settled on a particular choke. It also improved my shot confidence - I knew exactly what to expect in terms of terminal performance which helped me better gauge shooting distances and efficacy in the field.

As far as the restriction of the choke itself is concerned (not referring to the make or model of the choke, like a Carleson’s Cremator choke tube, but its actual diameter), it’s important for a hunter to be realistic about their shooting expectations and typical hunting scenarios to then judge appropriate choke selection based off its consitriction. For those that intend to only take shots under 25 yards, an Improved Cylinder or Skeet choke is going to be ideal. The application here would be for when shots are only taken when waterfowl are decoying close to the hunter. On the other end of that same spectrum, goose hunters in field blinds may be taking further pass-shots at longer ranges like 40 yards, Improved Modified would be more appropriate.

The nuances of the various diameters can be argued ad nauseam and, interestedly enough, some choke tube manufacturers have gravitated towards a more simplified designation of effective distance with their proprietary offerings. For example, Patternmaster has some choke tubes that are referred to a as “mid-range” or “close-range,” instead of the more traditional terminology like “Modified” or “Improved Cylinder.” I suspect this is part marketing ploy, part placation of the old-school shotgunning purists as many of these chokes that tout a name like “mid-range” will have a documented constriction that doesn’t quite fit perfectly with standardized constrictions. An example of this would be Carleson’s Cremator Long Range choke, which is maximized for ammunition that utilizes steel shot, that has a diameter of 0.695 inches. Given that a Full choke is typically 0.699, and an Improved Modified choke is typically 0.705, this particular tube doesn’t quite align with the standardized naming convention, thus labeling it as such would be something of a misnomer. While diameters are standardized for good reason, in this case, it’s appropriate to have a non-typical name, like “Long Range,” as the diameter is in fact, different from the standardized naming convention and its respective diameters.

It never hurts to have options which is why I am a fan of Carleson’s Cremator 3-tube set. By packing these in my blind bag, I have the option, mid-hunt, to swap out tubes. This gives me the flexibility to adjust spacing between the blind and decoys, as well as adapt to how the ducks are flying, and responding to calls and decoys, that day.

In short, choke selection can be narrowed down by understanding its application but cannot be completely refined until a patterning exercise is conducted, where different shot shell loads are put through various chokes, from the same gun, at the same distance. For Marilyn, I have a three choke set that covers all my bases: a close range, a mid-range, and a long range. I keep the mid-range in the gun with the close and long-range tubes in my blind bag for quick access while I’m on the road. For most of my duck hunts, where I setup decoys and hunt from a makeshift blind or natural cover 20 yards nearby, my mid-range tube gets the most action. I will then switch, to tighten up the pattern further or loosen it up more, depending on how the hunt is going. Sometimes, ducks just don’t like what you’re selling, and they flare from the decoys a little too soon. In which case, I’ll swap out to the long-range tube. Other days, especially during teal season, I’ll swap out for the close-range tube. Having the flexibility to do this mid-hunt is a huge asset which is why I recommend getting a three-tube set like this Carleson’s Cremator set. But, if only one tube is in the budget for right now, choose the tube that is most appropriate for your style of hunting and species of pursuit.

Bead

Before prescribing a recommendation for what a bead should, or shouldn’t, be, we need to take a step back and consider the mechanics of wing shooting and how that differs from point-target shooting (such as shooting a rifle at a deer, or a pistol at a paper target). Shooting, in most disciplines, is thought of as a static activity. The shooter, be it standing, kneeling, or forming any other body-shape, remains in a static position while discharging the respective firearm. The shooter typically uses a reference point, found on the gun itself, which would be referred to as a “gun sight,” to orient themselves and their firearm so that, upon discharging the firearm, the projectile will travel in such a manner that it will arrive at the intended destination (such as a bulls-eye on a target or in the vitals of a deer). Wingshooting, on the other hand, calls for the shooter to be anything but static! To make an effective shot on a flying clay or bird, a shooter must “point” their shotgun, instead of aiming, while simultaneously swinging the shotgun in a manner that follows the target. Just as the mechanics of taking a shot are different between shotgun and rifle, or wing-shooting and target shooting, the gun sights need to be treated differently as well.

Here is an archetype shotgun bead: a simple, metal sphere positioned at the center of the bore. This is on a 100-year-old Sears & Roebuck bolt action 20 gauge that was my grandfather’s. I killed my first wild pheasant with this shotgun!

A rifle or a pistol will typically have a front and rear sight and, when the shooter lines both of these up, the shooter can expect the firearm to perform in a specific manner (e.g, sending a bullet down range smack into the center of the bulls-eye on the target). Shotguns for wing-shooting, on the other hand, will sport a single bead and instead of the shooter relying on this bead to line up with the target in a certain manner to achieve a certain terminal result, the shooter, instead, relies on this bead to ensure that the shotgun’s bore is centered and the shotgun is properly mounted into the shooter’s shoulder. Another way to think about this would be to consider, with a rifle or pistol, that the shooter is going to adjust their static body position to align with the firearm. That, in turn, will help deliver the desired results down range. Shotgunners are going to orient the gun to themselves, using that bead as a reference point to do so, so that the shotgun can server as a fluid extension of the arm and be effectively “pointed” at a target, much like a person might point their finger at a bird in flight (and following that bird with their finger as that bird travels in the air).

It’s worth acknowledging that some shotguns will have two beads, one at the end of the bore and one about mid-way, but they are intended to be treated the same as a single bead: a reference point for the bore so that the shooter is ensuring that the gun is mounted properly. The matter of having one or two beads on a shotgun is something of personal preference but most shotguns today are manufactured with a single bead. Many shooters find that the second bead creates an “extra thing” for the eye to track and process whereas the single bead is just that - one single reference point for the eye to locate. If we think about how a Blue-winged teal, how it can fly nearly 40mph, and how a duck hunter will need to mount their shotgun, point and track that teal, and squeeze off a shot… there’s not a lot of time for “extra thinking,” so to speak, which is why I am a proponent of a single bead over a double bead.

I have a beautiful 28 gauge Benelli Legacy that has two beads and, even after lots of practice, I still catch myself lingering a touch too long on a flushing quail while my eyes are looking for the intended alignment of the two beads before the shot.

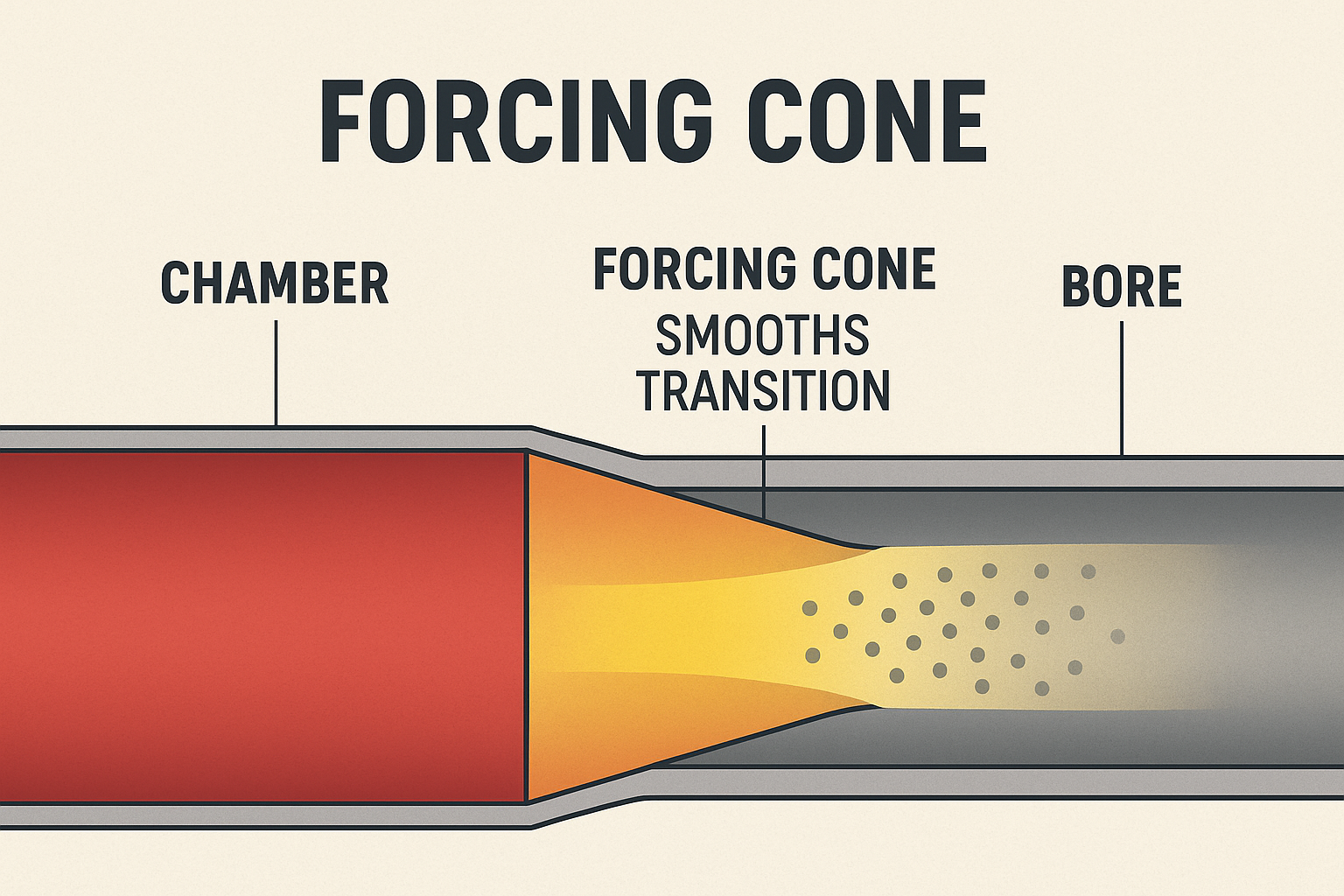

Forcing Cone

The forcing cone in a shotgun, which is located between the chamber and the bore, serves the gun by tapering the shot as it exits the shell and passes into the bore - it’s a funnel. A funnel consists of the mouth, cone, neck, and spout. If you’re using to pour gasoline into a lawnmower, the gasoline enters the mouth, tapers through the cone, travels down neck, and out of the spout. In our case, that means the shot departs from the shell and exits the chamber, entering the the mouth of the forcing cone. The shot then gradually constricts through the cone and enters the bore. The length of the neck, along with the angle of the cone (e.g. the sharper angle, the shorter forcing cone) can influence how pellets are constricted and passed into the bore.

The reason I call attention to it here is not to discuss whether or not to get a forcing cone, because all shotguns already have one, but whether or not to have a gunsmith make adjustments to it. The theory is that by lengthening the forcing cone beyond what the manufacturer originally provided, pellets will have less deformation as they enter the bore due to a more gradual transition. Think about a bunch of people trying to get into a sporting event stadium through a single gate. Inevitably, people are going to be bumping into one another, crowded, pushing to get into the gate before the big game starts. But, if the path into the gate is tapered, a more organized flow can be had to admit spectators. Swap spectators for shot shell pellets, and you get the idea.

As the shot leaves the hull, it will pass through the forcing cone before entering the bore. The forcing cone tapers the fired shell’s payload and smooths the transition from chamber to bore.

Before the 2000’s, getting a gun’s forcing cone lengthened was strictly handled by a gunsmith and the jury was out for quite some time on whether or not it was beneficial. You can still find online forum posts where one guy says it (having a gunsmith lengthen the forcing cone in his shotgun) changed his life and they next disputing the benefit. Since then, manufacturers have spent some time and energy determining that a lengthened forcing cone, say 3” from the previously standard 1.5”, could reduce felt recoil and pellet deformation, as well as improve overall patterning.

Browning was the first manufacturer to call attention to offering a “longer forcing cone” with their Maxus shotguns and some Citoris in the early 2000’s. By the 2010’s, Beretta and Winchester were all touting some form of lengthened forcing cone while Benelli entered the chat in 2024 with it’s Advanced Impact system available in Super Black Eagle 3 and Ethos product lines.

I purchased Marilyn, a Benelli M2, years before Benelli’s A.I. roll out, so there’s likely some lengthening that could be done by a gunsmith like Rob Roberts Gunworks, but it’s just something I haven’t had done [yet]. It, like so many others, falls on my list of, “I’d like to do that, I just haven’t gotten around to it yet.” I think, for older guns like mine, the service is worth the investment (about $150 with shipping to and fro) but for those that are in the market for a new gun today, there are several great options out of the box that already address this.

Oversized controls can make a world of difference to the chilly duck hunter.

Cold duck hunts = warm gloves. Warm gloves = bulky. Bulky = loss of dexterity when manipulating a safety, racking or releasing a bolt. Oversized controls can help overcome this problem.

In the next few photos, you’ll notice a trend - bigger is better. This isn’t typically the case with anything in life but, when it comes to manipulating the controls of a shotgun while wearing bulky, dexterity-killing winter gloves, bigger IS better. I installed an oversized charging handle, bolt release, and safety myself. I’m no gunsmith but I found each of these to be relatively plug-and-play with the help of a Youtube video or two. There’s quite a few after market options out there now for each of these but I ended up getting mine from Taran Tactical.

Similar to the forcing cone discussion, many manufacturers now offer shotguns with oversized controls. Here’s a few:

Charging Handle

This oversized “pineapple grenade” charging handle is a bit longer than the factor handle. It’s wider footprint, with its textured face, is significantly easier to grip than the factory handle when wearing gloves. Note the oversized bolt release to the right of the charging handle as well.

Bolt Release

This oversized bolt release, about 1/3rd the size bigger than the factory, is easier to “find” while wearing thick, winter gloves. Note the Match Saverz shell holder in the frame as well.

Safety

This oversized safety has about the same footprint as the factory safety, but it has a deeper knob. Even though only slight, the further protrusion from the trigger well makes “finding” the safety much quicker, especially when wearing heavy, winter gloves.

Trigger

The amount of forced required to pull a firearm’s trigger back is measured in pounds of force and is typically referred to as, “trigger pull weight.” There’s a Goldilocks poundage to a shotgun’s trigger, where the trigger is heavy enough that it’s not going to startle you when it fires and still light enough that you don’t find yourself burning excess calories just to take a shot, and is thus, “just right.” However, for a waterfowl gun, I’ve found the stock trigger weight from the factory to be adequate in most cases (in my case, Benelli set my M2 to 4.5 pounds).

Competition rifle shooters will make trigger adjustments a priority. In that environment where shots are premeditated and controlled, an extremely light trigger pull weight can be advantageous (competition rifle shooters will often set trigger weights as low as one pound). But for the duck and goose hunter, the environment is quite a bit different. Often, thick gloves are worn, which can degrade tactile feel and dexterity, and shots can be quick and reactive, so having a lightened trigger can, potentially, be a bit risky. The extra fabric from the gloves inside the trigger well could potentially, if a trigger was set light enough, press against the trigger far enough and discharge the shotgun a moment sooner than planned. This isn’t said to discourage anyone from adjusting the pull weight, but just sharing for consideration that a light trigger may not be all that helpful for this application.

The pull weight isn’t everything, though, when it comes to considerations of the trigger.

Triggers can wiggle and they can creep; both are qualities most shooters would prefer to avoid. A trigger that wiggles (think, perpendicular motion to the direction that the trigger travels) is indicative of poor machining tolerances that could develop into a bigger problem later in the shotgun’s life. Any substantial wiggle warrants further review by a gunsmith.

The term, “creep,” is a term used to describe the amount of travel a trigger has before it hits what’s referred to as a “wall.” Think of the wall as the tipping point, or the straw that breaks the camel’s back. When squeezing the trigger, a certain amount of force (the trigger pull weight) must be applied. As force is increased, the trigger will travel further back into the trigger well until, finally, enough force is applied and the sear is released, sending the hammer down onto the firing pin which ignites the primer of the shotgun shell. Often creep and trigger weight go hand in hand, where a light trigger pull will have very little travel, or creep, but this is not always the case.

An experienced shooter does not want to expend an inordinate amount of energy just to squeeze the trigger, neither do they want to spend a great deal of time to squeeze the trigger, either. The question of time spent, in this regard, is both functional from a shooting phsyiology standpoint, as it is in a practical application of shot opportunity. The moment in time when the firing pin strikes the shell is critical. The timing of this is one of the many variables a wingshooter is striving to get “just right” so that the target is hit at the intended time and place. If it takes an awkward amount of time to squeeze the trigger, an opportunity may be missed. Just as if it takes a great deal of energy, an opportunity may be missed, as well. Take a moment to exaggerate the action of squeezing the trigger. What happens when a ton of force is needed? The body compensates and it can become difficult to maintain a smooth swing and control of the shotgun.

I’ve found that most reputable modern auto loaders have a reliable, consistent trigger out of the box that most will be satisfied with. However, don’t let me opinions sway you on the matter. If you’re trigger feels clunky, or you’re just simply curious by the matter, talk to your gunsmith about filing down a sear or two to smooth out the pull; or perhaps look for a trigger assembly upgrade from a reputable after market source.

Recoil Spring

I’ve found that shotgun recoil springs are more a topic of interest for competitive shooters than they are for duck hunters. That said, I did replace Marilyn’s recoil spring after six years years and thousands of target and duck loads down the tube. I noticed that my bolt carrier group was a bit sluggish on the return and, through a series of troubleshooting steps, elected to try a new recoil spring. There was about a 1.5” difference between the original spring and the factory replacement (the replacement being the longer of the two). This is likely not an issue for most hunters but something I wanted to call attention to here that, if you’re auto loader starts to feel sluggish after several years (and several thousand shells) and you’ve deep cleaned the heck out of it a few times over, you may need a new spring. Good news, a new recoil spring is one of the cheaper things to replace on a gun.

Match Saverz

I’m a sucker for a good action flick and there’s something downright entertaining about John Wick shoot-em-up franchise. The sophomore film of the franchise features a Benelli M2, wielded by Keanu Reeves, in the catacombs scene. I’ll spare you the gory details but you can see what I’m talking about here, at minute 2:44, the gun runs dry…but worry not! Keanu, in a blink of an eye, grabs the spare shell held in place by a Match Saverz mounted on the receiver and gets the bad guy. And so I got an idea… I thought back to how many times I’ve fumbled for another shell, after emptying my gun on a flight of ducks across the decoys, or when jumping a pond. I bet that would come in handy.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service has a regulation, regarding hunting migratory birds, that no more than three shells can be in your gun at any time

“With a shotgun of any description capable of holding more than three shells, unless it is plugged with a one-piece filler… so its total capacity does not exceed three shells.” - 50 CFR § 20.21(b)

I went through a flat of target loads before I had the mechanics down, and then another flat with gloves on. I admit, this is a bit excessive, but it was a lot of fun to practice and now, every once in a while, it comes in handy to be able to quickly grab a fourth shell, drop it into the open receiver, and hit the bolt close.

Accoutrements

We’ve covered most of the goodies but I don’t want to wrap up without acknowledging the value of a gun case and gun sling. Moisture and guns don’t mix and that can be tough to avoid on a duck hunt but that doesn’t mean a hunter can’t take some precautions to mitigate how much moisture comes into contact with their gun. I recommend a floating, water proof case so on your trek into or out of the marsh, or on the boat ride, your gun is contained. Should it fall off the boat or out of whatever you might be using to transport your decoys and other equipment to the location of the hunt, you’ve got a fighting chance of recovering your gun instead of watching it sink beneath the surface.

Similarly, during the hunt itself, having a sling can be very handy. For those that aren’t fortunate enough to have a good gun dog on hand, duck recovery often means moving the boat or getting out of the blind and walking around the marsh but you never know when a duck might just appear, or if there’s a cripple paddling away that needs a follow-up shotThere’s also plenty of times when decoys need to be adjusted or adjustments need to be made to the blind and having two hands would be awfully convenient. Enter, the sling. Any sling will do but I’d recommend something synthetic that won’t fray (nylon) or crack (leather) from prolonged use. You can always take it off and tuck it away in the blind or in your gun case if you find that it interferes with your shooting, but I’d rather have it available than not when I’m in the marsh.

In Conclusion

If you made it this far, I tip my hat to you for your commitment to slug through all ~3,000 words. I worked on this piece of writing off and on for over a year and, candidly, it got a bit out of hand. But I simply couldn’t find a more concise way to explain, “I recommend this choke” without also explaining, “by the way, this is what a choke is,” for example.

As mentioned periodically throughout this piece, there are several great options on the market today that incorporate many of the things I’ve done to my own gun over the years. Many of these were not available out of the box when I bought my M2 a decade ago. Or, what was available, was only found on high-end “custom shop” offerings so instead of spending $3,000+ on a top tier Benelli custom shop gun, I spent about $1,000 and then another few hundred bucks over the years making the various minor upgrades and changes.

At the end of the day, the gun doesn’t make the hunt. Guns are tools and they can be a lot of fun to collect, shoot, and tinker with, but don’t lose sight of what matters most: time afield.

Gun Benelli M2 Field, 12 Gauge

Nickname Marilyn the Mallard Mauler

Choke(s) Carlson’s Creamator, Ported (3 Tube Set: Close Range - Mid Range - Long Range)

Ammunition of Choice: Remington Peterson’s Blue (no longer manufactured), Kent Fasteel 2.0

Modification(s): Oversized Bolt Release, Oversized Charging Handle, Oversized Safety, Extended Carrier, Aluminum Magazine Follower, Match Saverz External Shell Holder, Swivel Sling Mounts

Aldo poses with pride, chest puffed (burs and all), showing off a Kansas three-man limit of ducks.